Financial Theater: What the F1 Movie Was Really Selling

When critics rave about a movie with a plot so terrible it borders on satire, you're not witnessing the failure of film criticism; you're witnessing its perfect success. The F1 movie wasn't made for moviegoers. It was a $300 million marketing campaign disguised as entertainment, engineered for an audience that would never buy a ticket but might buy the entire sport.

The racing footage was genuinely spectacular; every frame engineered to make you feel G-forces in your chest, cinematography that would make Jerry Bruckheimer proud (he produced it, after all). But strip away the visual dazzle and you're left with Days of Thunder meets Top Gun meets Point Break, except those classics had heart and characters you actually cared about. This was Brad Pitt. Who was great, as always, carrying a formulaic sports movie through every predictable beat from the Bruckheimer playbook. The absurd racing strategy where Pitt's character intentionally crashes into other cars so his teammate could score points had me almost giggling in the theater. Any legitimate F1 fan who actually watches qualifying sessions and follows car upgrades between races would find it laughably unrealistic.

The fact that critics and audiences got swept up in spectacular racing footage while completely ignoring the terrible plot wasn't an accident; it was exactly the point. When something this expensive succeeds this predictably despite being narratively bankrupt, you have to ask: what was it really designed to accomplish?

The answer becomes clear when you understand the real audience. Sitting in that theater, watching the perfect execution of financial theater designed for an audience of maybe fifty people worldwide, I realized I was witnessing something far more sophisticated than bad filmmaking. I was watching Liberty Media's most expensive advertisement ever created.

The Art of Signaling Without Selling

Liberty Media, which owns Formula One through its tracking stocks (FWONA, FWONB, and FWONK), has been the subject of serious acquisition interest. In 2023, Saudi Arabia's Public Investment Fund reportedly offered over $20 billion for the series; a bid that Liberty rejected not because they weren't interested in selling, but because they knew they could engineer a better price.

Here's the elegant part: while Liberty Media benefited enormously from this marketing campaign, it was actually Apple that footed most of the production costs through Apple Original Films. This represents financial engineering at its most sophisticated; Liberty essentially got someone else to finance their most expensive advertisement ever created, while Apple got a prestigious blockbuster to establish their theatrical credibility. Every spectacular crash, every perfectly lit garage scene, every moment of Brad Pitt's character staring pensively at a racetrack served Liberty's purpose of demonstrating Formula One's cultural relevance to potential buyers.

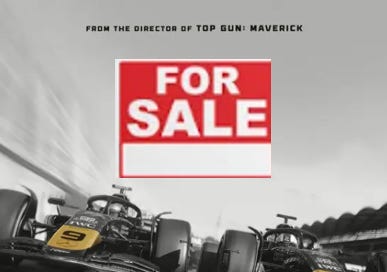

In the world of high-stakes corporate transactions involving sovereign wealth funds and private equity titans, you don't put up a "For Sale" sign. You don't hire Goldman Sachs to run a formal process. Instead, you create signals. You manufacture momentum. You flood the market with evidence of your asset's continued growth and cultural relevance.

John Malone, Liberty Media's chairman and the subject of the investor classic "Cable Cowboy," has spent decades mastering the art of financial architecture. He's built empires through leverage, rolled up industries through strategic acquisitions, and created value through structural engineering that most investors can't even comprehend. When a master of capital allocation like Malone starts positioning an asset for maximum visibility, it's not because he's fallen in love with the product. It's because he's preparing for the exit.

The F1 movie accomplished exactly what it needed to accomplish. It demonstrated global reach; $144 million worldwide suggests the sport can sell beyond its traditional European strongholds. It proved Hollywood's A-list talent wants to associate with the brand. It generated months of sustained media coverage. Most importantly, it created a tangible artifact that potential buyers could point to when justifying a $25 billion, $30 billion, or $35 billion valuation to their investment committees.

The Buyers Who Play by Different Rules

The buyers Liberty Media is courting operate with fundamentally different incentive structures than traditional corporate acquirers. Sovereign wealth funds like Saudi Arabia's PIF, Qatar's QIA, or Singapore's GIC don't mark their investments to market quarterly. They don't face activist investors demanding short-term returns. They don't need to justify every dollar spent to public shareholders scrutinizing earnings calls.

This creates what I call "volatility laundering"; the ability to pay seemingly irrational prices for prestige assets because those assets exist outside traditional valuation frameworks. The financial volatility gets absorbed into balance sheets so vast that billion-dollar fluctuations barely register, while the strategic value compounds over decades rather than quarters. These assets often serve as collateral for much larger financial strategies, a dynamic I explored in more detail in my recent piece on tokenization and systemic risk.

What's particularly sophisticated is how volatility laundering has essentially become its own asset class. Own assets that generate returns without volatility markdowns, even during earnings declines. Unless there's severe impairment, asset values hold steady or appreciate immediately after changing hands. The new buyer can then borrow against this "stable" asset value to fund additional investments. It's a self-reinforcing cycle; because assets maintain their values and can be borrowed against, no one needs to sell assets anymore to free up cash for new acquisitions. They just keep borrowing, using appreciating prestige assets as collateral for the next deal, and the next, creating a daisy chain of leverage built on assets that may never face true market-based price discovery.

Look at the playbook in action across the sports world. When Saudi Arabia's PIF acquired Newcastle United for $400 million in 2021, they weren't just buying a football club; they were buying a platform for global influence that operates parallel to traditional diplomacy. Qatar proved this model works by purchasing Paris Saint-Germain in 2011, then using it as a strategic asset during their 2017-2021 diplomatic crisis with Saudi Arabia. While formal diplomatic channels closed, PSG still played, Qatar Airways still sponsored, and Al Jazeera still broadcast. The sports infrastructure became a parallel diplomatic network that functioned regardless of political tensions.

These acquisitions represent influence operations disguised as investments. Qatar's strategy expanded beyond football with QSI's $4.05 billion investment in Monumental Sports & Entertainment in 2023, securing stakes in the Washington Wizards, Capitals, and Mystics. The UAE followed suit with Manchester City through Abu Dhabi United Group. Each purchase creates a web of relationships with multinational corporations, government officials, and cultural elites that traditional diplomacy simply cannot access.

The Perfect Storm for Sports Properties

The timing couldn't be better for sellers like Liberty Media. The sports industry is experiencing a transformation that makes Formula One's positioning perfect. The NBA just closed an 11-year, $76 billion media rights deal that averages $6.9 billion per season. The Los Angeles Lakers sold for $10 billion to Mark Walter (capturing their 17 championships, though 5 of those were won as the Minneapolis Lakers before moving to LA), who already owns the Dodgers and is building a multi-franchise entertainment empire.

Sports properties are commanding unprecedented valuations as streaming services and traditional networks compete for live content that viewers can't skip, fast-forward, or pirate. Traditional buyers worry about revenue multiples, cash flow generation, and return on invested capital. Sovereign buyers care about prestige, global reach, and strategic positioning. When you're selling to the second group, financial engineering becomes less important than narrative engineering.

Look at what Mark Walter has built around the Dodgers. The team became the foundation for a broader sports and entertainment empire that now includes the Lakers, the Sparks, interests in Chelsea FC, and the Cadillac Formula One team. This isn't sports ownership; it's portfolio construction. Walter understands that the most valuable sports properties aren't just teams or leagues. They're platforms for building integrated entertainment experiences that span multiple demographics, geographies, and revenue streams.

If I had to speculate, and I will, Walter's next move involves someone like Bob Myers, the former Warriors GM who built championship teams through systematic talent evaluation and organizational culture. Prestige attracts talent, valuation supports leverage, and leverage buys the freedom to bet on a bigger canvas. You don't just buy one team. You build a portfolio. You cross-sell, structure, refinance, repeat. The stadium becomes the storefront. The players become the content. The narrative becomes the currency.

The Future of Sports Entertainment

The future of sports entertainment looks nothing like what we've known for the past fifty years. The traditional model of selling tickets, selling concessions, selling broadcast rights feels quaint compared to what's coming. The next generation of sports properties will be immersive, personalized, and dynamic. And this is where those seemingly insane valuations start to make sense.

Would you rather have nosebleed seats in section 304 with an obstructed view for an NBA playoff game, or pay the same amount to ride along with Lewis Hamilton when the constructor's championship is on the line? What if I want season tickets not to a team, but to a player? A Curry "pass" that follows Stephen Curry's entire season: practice footage, pre-game rituals, real-time biometrics during games, post-game interviews.

What if my son, who worships Steph, gets a custom highlight reel and a virtual shooting clinic with him for his birthday? The kind of personalized experience that makes you understand why certain moves never leave you, even decades later. What if halftime isn't a recycled mascot dance but an experience moment; watch five minutes of a sponsor integration and enter to win a cruise, or plug into a celebrity coach's mic'd-up timeout breakdown as a paid tier. If I watch enough games through the Curry "pass," maybe I get a loyalty badge, a one-on-one AMA in the metaverse, or exclusive access to early apparel drops.

The community layer transforms everything. What about viewing parties from home with synced camera angles? Multi-sport passes that let you jump from NBA to F1 to MLS with friends and family across devices, with group chats embedded on-screen? You're not just watching anymore; you're hosting. The medium becomes inherently social rather than isolating.

Even advertising evolves beyond recognition. Maybe you don't want ads; you pay to turn them off. Or maybe you lean in completely. Verstappen's car flashes a Heineken logo during the race; tap to shop, tap to get DoorDash to deliver the beer to you as you watch, tap to earn points, tap to unlock a temporary merch discount. Richard Mille on Leclerc's wrist gets tapped by 50,000 viewers simultaneously, generating more engagement than a Super Bowl spot. Dynamic product placement becomes a revenue stream that dwarfs traditional sponsorship.

Extend this logic to behavioral monetization: if I stay past the third quarter, I unlock a rebate on concessions. If I watch every Lakers game for a month, I get access to a Discord with exclusive team updates or first looks at trade rumors. If I attend five Formula One races in a season, I get access to a private paddock experience at the sixth.

This isn't theoretical; the technology exists today. What's missing is the capital to implement it properly and the vision to execute it at scale. When the Lakers sell for $10 billion, you're not just buying 17 championships and LeBron James. You're buying the platform to build these experiences for millions of fans who will pay premium prices for premium access. The revenue potential from personalized, immersive sports experiences could be 10x what traditional broadcasting generates.

Traditional sports ownership groups, families who bought teams decades ago, local businessmen who treat franchises as trophies, don't have the resources, appetite, or incentive structures for this kind of transformation. But sovereign wealth funds and private equity titans do. They can afford to lose money for five years while building the infrastructure for the next twenty years. More importantly, they can afford to ignore quarterly earnings volatility while their investments compound over decades.

Why "Bubble Pricing" Misses the Point

This is the crucial distinction that traditional analysts miss when they call these valuations "bubble pricing." Saudi Arabia's PIF managing $700 billion in assets can absorb years of losses on a $25 billion Formula One acquisition if that acquisition delivers strategic value across multiple decades. The fund doesn't need Formula One to generate 15% annual returns; it needs Formula One to generate influence, relationships, and optionality that support much larger strategic objectives.

The same logic applies to private equity buyers, though with different motivations. They're not buying entertainment assets to hold forever; they're buying them to transform the underlying business model, extract maximum value through operational improvements and financial engineering, then exit at multiples that reflect the enhanced cash flow generation. The personalized, immersive experiences I described aren't just better for fans; they're dramatically more profitable for owners.

The F1 movie mattered so much to potential buyers because it wasn't just evidence of the sport's current popularity. It was a preview of what Formula One could become under the right ownership structure. The production values, the global distribution, the celebrity endorsements, the seamless integration of Hollywood glamour with motorsport authenticity; all of it demonstrated that Formula One could support the kind of premium, personalized entertainment experiences that represent the future of sports media.

The movie's success also validated Liberty Media's broader strategy of treating Formula One as entertainment first, sport second. Netflix's Drive to Survive made the drivers into characters. The Las Vegas Grand Prix made the races into events. The F1 movie made the entire sport into a franchise. Each step moved Formula One further away from its roots as a European motorsport and closer to its future as a global entertainment property.

For potential buyers, this progression isn't just encouraging; it's essential. Sovereign wealth funds aren't interested in buying niche sports properties. They want global brands that can anchor much larger strategic initiatives. Formula One fits that description perfectly. It's international by definition, premium by design, and glamorous enough to attract the kind of high-net-worth individuals that sovereign funds want to cultivate.

The Saudi PIF's interest in Formula One should be understood in this context. The fund already sponsors races, backs teams, and has deep ties throughout the sport. Acquiring Formula One outright would give Saudi Arabia a platform for projecting influence across six continents, relationships with dozens of multinational corporations, and access to the global elite who populate Formula One events. From a strategic perspective, that's worth far more than any traditional financial return.

The F1 movie was designed to amplify exactly these qualities. Every glamorous paddock scene, every celebrity cameo, every spectacular racing sequence reinforced the message that Formula One represents the intersection of technology, wealth, and global culture. For buyers looking to purchase influence rather than just entertainment, that positioning is invaluable.

The Endgame

Liberty Media's timing couldn't have been better. The buyers most likely to acquire Formula One aren't traditional private equity firms; they're sovereign wealth funds with consortium partners that read like a who's who of global wealth and Formula One obsessives. Think Brad Pitt (who's already invested in the sport through the movie), current and former drivers, founders of the biggest hedge funds and PE firms, and billionaires like Bezos and Ballmer who love Formula One and extreme sports. Private equity is flooding into sports at every level, but Formula One is the kind of trophy asset that attracts the ultra-wealthy who want both financial returns and cultural influence. The combination of streaming wars, international expansion, and demographic shifts has created a perfect storm for sports properties with global reach and premium positioning.

Formula One checks every box. It's global by design, with races across six continents. It's premium by nature, attracting wealthy audiences that advertisers covet. It's growing rapidly in key markets, particularly the United States and Asia. Most importantly, it's controlled by a single entity, making acquisition straightforward compared to fragmented leagues with multiple owners.

The next few months will be crucial. The current Formula One season is shaping up to be one of the most competitive in years. Max Verstappen might not win his fifth straight championship, with McLaren drivers Oscar Piastri and Lando Norris leading the points race. The sport's popularity continues growing, particularly in the United States where three races are now scheduled annually. Most importantly, the F1 movie's success has created a narrative of momentum that potential buyers can point to when justifying premium valuations.

Speaking of mentors and the dynamics they create, the movie's hollow mentor-student plotline might have been terrible storytelling, but it perfectly reflects the real-world power structures these buyers are actually purchasing. If you want to understand how these relationships really work in practice, check out my recent piece on the mentors who shaped my career; the real stories are far more complex and interesting than anything Hollywood could manufacture.

What's certain is that the F1 movie accomplished exactly what it was designed to accomplish. It wasn't created to win Academy Awards or launch franchises. It was created to demonstrate that Formula One had evolved from a motorsport into a global entertainment phenomenon capable of supporting the kind of premium, personalized experiences that represent the future of sports media. This was better than any pitch book or investment banker's auction process; this was the start of a beauty contest, complete with A-list endorsements and global media validation.

The racing was spectacular. The box office was massive. The reviews were positive despite the hollow storytelling. But the real success had nothing to do with box office receipts or critical acclaim. The real success was creating a $300 million advertisement for Formula One itself, timed perfectly for a moment when the world's wealthiest buyers are actively looking for exactly the kind of asset that Formula One has become.

The movie was never about the movie. It was about what comes after the credits roll. In the world of high-stakes financial theater, where entertainment assets serve as vehicles for volatility laundering and geopolitical influence, that's exactly how you'd want to write the script. The hollow plot wasn't a bug; it was a feature. Pure spectacle, engineered for maximum impact on the only audience that really mattered: the buyers with enough capital and long-term vision to transform these valuations from seemingly irrational to inevitable.

When Formula One eventually sells for a premium valuation that defies traditional analysis, remember this moment. Remember the movie that wasn't really a movie, but a perfectly crafted piece of financial theater designed to justify a price that conventional metrics couldn't explain.

The future of entertainment isn't about telling better stories; it's about creating better platforms for monetizing human attention and community. In that context, the F1 movie's hollow plot wasn't a failure of storytelling. It was a feature, not a bug. Pure spectacle, engineered for maximum impact on the only audience that really mattered: the buyers with enough capital and long-term vision to transform these valuations from seemingly irrational to inevitable.

The F1 movie was never about entertainment. It was about what comes next. And what comes next is the financialization of everything we love, wrapped in spectacular cinematography and sold to us as progress. The movie was just the opening act.